Overfeat:

Classification, Localization

1. Introduction

Object classification, localization, and detection remain significant areas of interest in modern computer vision research. The concepts of classification and localization can be roughly described as labeling the object, describing its category, and then providing the location of the object within an image. Achieving these objectives with high accuracy and efficiency could pave the way to many potential technological innovations: self-driving vehicles, medical image reading for diagnostics, and satellite imaging for natural phenomena predictions are only a few examples.

In our project, we investigate object classification and localization based on the seminal work, Overfeat: Integrated Recognition, Localization and Detection Using Convolutional Networks [1], by Sermanet et al. The Overfeat model achieves state-of-the-art performance on object detection tasks, demonstrating the effectiveness of CNNs for object detection. Since then, numerous variants of CNN-based object detection models have been proposed, each with its own unique set of strengths and weaknesses.

1.1. Related Work

In the field of object detection, several papers have been inspired by Overfeat and have extended its work:

- Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks by Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He, Ross Girshick, and Jian Sun, which introduces the Region Proposal Network (RPN) to improve the speed and accuracy of object detection.

- Single-Shot Detection for Real-Time Object Detection by Wei Liu, Dragomir Anguelov, Dumitru Erhan, Christian Szegedy, and Scott Reed, which introduces the Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD), a method for object detection that is both accurate and computationally efficient.

- The precursor to OverFeat and related works is the paper by Felzenszwalb et al. titled Object Detection with Discriminatively Trained Part-Based Models published in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence in September 2010 [2].

2. Methodology

The model integrates three objectives. In ascending order of complexity and subtask relationship, they are classification, localization, and detection. Classification is the simplest task, whereby a given image is guaranteed to contain an instance (we define an instance as an object that we are interested in for the purpose of the task) that the model must label. Localization contains the task of classification, whereby an image containing an instance is given, and the model must classify the instance and produce an estimate for where the object is in the image. In the Overfeat paper, the object is localized through a bounding box. More advanced techniques could include segmentation, whereby the contour of the object is traced. The most complex task is object detection, whereby an image may contain no instances, one instance, or multiple instances, and the algorithm must classify and localize each instance that is present.

In our work, we follow the methodology outlined in the Overfeat paper, introducing three submodels. The Overfeat feature extractor produces a Tensor label, which is fed into two distinct models that perform classification and regression (localization) respectively. It became quickly apparent that an exact replication of the model proposed by the Overfeat paper would be infeasible given our resources and time allowance since the model failed to train for even one epoch on a dataset containing only a few hundred images (this was to test the validity of the model, final training for the model will be described in a later section and utilized a larger training sample set). Instead, we significantly reduce the size of the models. The models for the feature extractor (layers 1-5) and classification model (layers 6-8) are described in Figure 1. The model for the regression model is described in figure 2 (layers 6-8).

The Classification module also consisted of a sliding window technique of size (2,2), which allows for different max poolings at different scales across the image, capturing greater information about objects present in the image. Once trained, the bounding box predictions were then merged across other bounding boxes based on the paper’s criterion of a match score over 50% for intersection over union (IoU). Detection training was omitted.

Figure 1: Model architecture detailing the reduced Overfeat Extractor and Regression Layers

| Layer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | conv + max | conv + max | conv | conv | conv + max | full | full | Output |

| # Channels | 32 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 385 | 512 | 3 |

| Filter Size | 11x11 | 5x5 | 3x3 | 3x3 | 3x3 | - | - | - |

| Conv. Stride | 4x4 | 1x1 | 1x1 | 1x1 | 1x1 | - | - | - |

| Pooling Size | 2x2 | 2x2 | - | - | 2x2 | - | - | - |

| Pooling Stride | 2x2 | 2x2 | - | - | 2x2 | - | - | - |

| Zero-Padding size | - | - | 1x1 | 1x1 | 1x1 | - | - | - |

| Spatial input size | 221x221 | 24x24 | 12x12 | 12x12 | 12x12 | 5x5 | 1x1 | 1x1 |

Figure 2: Model Architecture for Feature Extractor and Classification Layers

| Layer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Output | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | conv + max | conv + max | conv | conv | conv + max | full | full | full | |

| # Channels | 32 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 770 | 1024 | 4 | |

| Filter Size | 11x11 | 5x5 | 3x3 | 3x3 | 3x3 | - | - | - | |

| Conv. Stride | 4x4 | 1x1 | 1x1 | 1x1 | 1x1 | - | - | - | |

| Pooling Size | 2x2 | 2x2 | - | - | 2x2 | - | - | - | |

| Pooling Stride | 2x2 | 2x2 | - | - | 2x2 | - | - | - | |

| Zero-Padding size | - | - | 1x1 | 1x1 | 1x1 | - | - | - | |

| Spatial input size | 221x221 | 24x24 | 12x12 | 12x12 | 12x12 | 5x5 | 1x1 | 1x1 |

2.1. Data

The dataset used in the model paper was the Microsoft COCO 2017 Object Detection [5] dataset that contained over 120000 images, 6600 of which we examined for training. Considering the resources available, we limited our scope to studying three instance classes relevant for the construction of a computer vision algorithm for self-driving vehicles: "car," "stop sign," and "traffic light." In addition to resource consideration, we note that the distribution of instances in the dataset is less than ideal as certain instance classes appear significantly more frequently in the dataset than others. Limiting our investigation to the three classes above restricts the number of samples from each instance to be about equal, improving the learning of the model.

Figure 3 (left) Classifier of the image outputs confidence for each location then sliding window enhances prediction. (right) Predictions are combined.

The preprocessing follows a similar approach to that in the paper. We first collect the image paths to all images containing relevant instances and their associated bounding boxes and one-hot encoding. Subsequently, we loop through each image and each of the bounding boxes. We resize the images to 300x300 (along with the bounding box labels) and crop around the area labeled by the bounding boxes. We impose the following restrictions for cropping:

- At least 50% of the bounding box should be contained in the image to reduce the noise of the data.

- The crop should be 221x221 pixels in dimension to unify input dimension to the model.

Imposing the above constraints, we may discover an area in which the 221x221 cropping may be extracted, typically larger than 221x221. Within this allowable area, we randomly crop 3 images for the training set and 2 images for the test set. The bounding boxes are then updated to reflect the cropping such that the bounding box specifically labels the portion of the instance remaining in the cropped image. The resulting cropped images are stored as numpy arrays. The numpy arrays, one-hot encoding, and bounding boxes are converted to .npz files and uploaded to the Google Colab directory for ease of access during training and evaluation.

2.2. Training

The training of the model follows the same structure from the Overfeat paper and consists of two stages.

Stage I

In stage I, the feature extractor is trained along with the classification model using Categorical Cross Entropy loss as the loss function with the weights trained using the Adam optimizer. We follow a reduced version of the heuristic described in the paper where for the first 10 epochs, we train the model with a learning rate of 0.001 followed by another 10 epochs with a learning rate of 0.0005. The original paper continues to refine training by halving the learning rate, but our work failed to produce appreciable improvement in classification loss and accuracy. Within each epoch, we apply random shuffles on the samples. Further, we impose random zoom and reflection on the images to improve the training.

Stage II

At the end of stage I, we arrive at a robust feature extractor and a classification model. In stage II, the output from the feature extractor is used as input to train the regression model to produce the bounding box. The feature extractor is no longer trained in this stage, and the regression model is trained with Mean Squared Loss. We again use the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001 for 20 epochs followed by another 20 epochs of training with a learning rate of 0.0005. We again utilize random shuffles on the samples.

3. Challenges

The computational resources required for this project posed a significant challenge. We began with an attempt at training the model using our local machines, but this proved to be difficult as the speed was insufficient and the devices began overheating and could not support extended training. To overcome this, we moved our model platform to Google Colab. There, the training improved, but we faced restrictions on the memory usage allowed; only through careful loading of models and declaration of variables could we support sustained training.

Additionally, even with data preprocessing, the input images remained relatively noisy. There are a couple of sources to the noise. First, some of the images were poorly labeled or mislabeled. Even by randomly selecting images and visualizing the associated bounding boxes, we could identify multiple incorrect labels or instances that were not labeled. Additionally, some of the labeled instances also were covered by additional objects. For instance, we identified an image of a car with the correct bounding box, but the body of the car is almost entirely obscured. There were also bounding boxes that were slightly larger or smaller than need be. These issues culminated in a relatively noisy dataset that could impact the training of the model. Since we ended up training the model on thousands of images, it was infeasible for us to manually verify or correct the bounding boxes.

Another challenge we faced came as we attempted to train the model for object recognition. This task entailed learning a generic “background” class so that the model would be able to distinguish when to make a prediction on object classification. However, this process added a significant overhead to our training, and we had to abandon this attempt.

4. Results

Our best training results thus far remain at a loss of 353.46 over 40 epochs (Fig. 4). We were careful to not overfit the data and leave space for the combination of bounding box predictions to occur.

The current regression model has a loss of 444.45 on the test data and the classification model has approximately 93% accuracy on the test data.

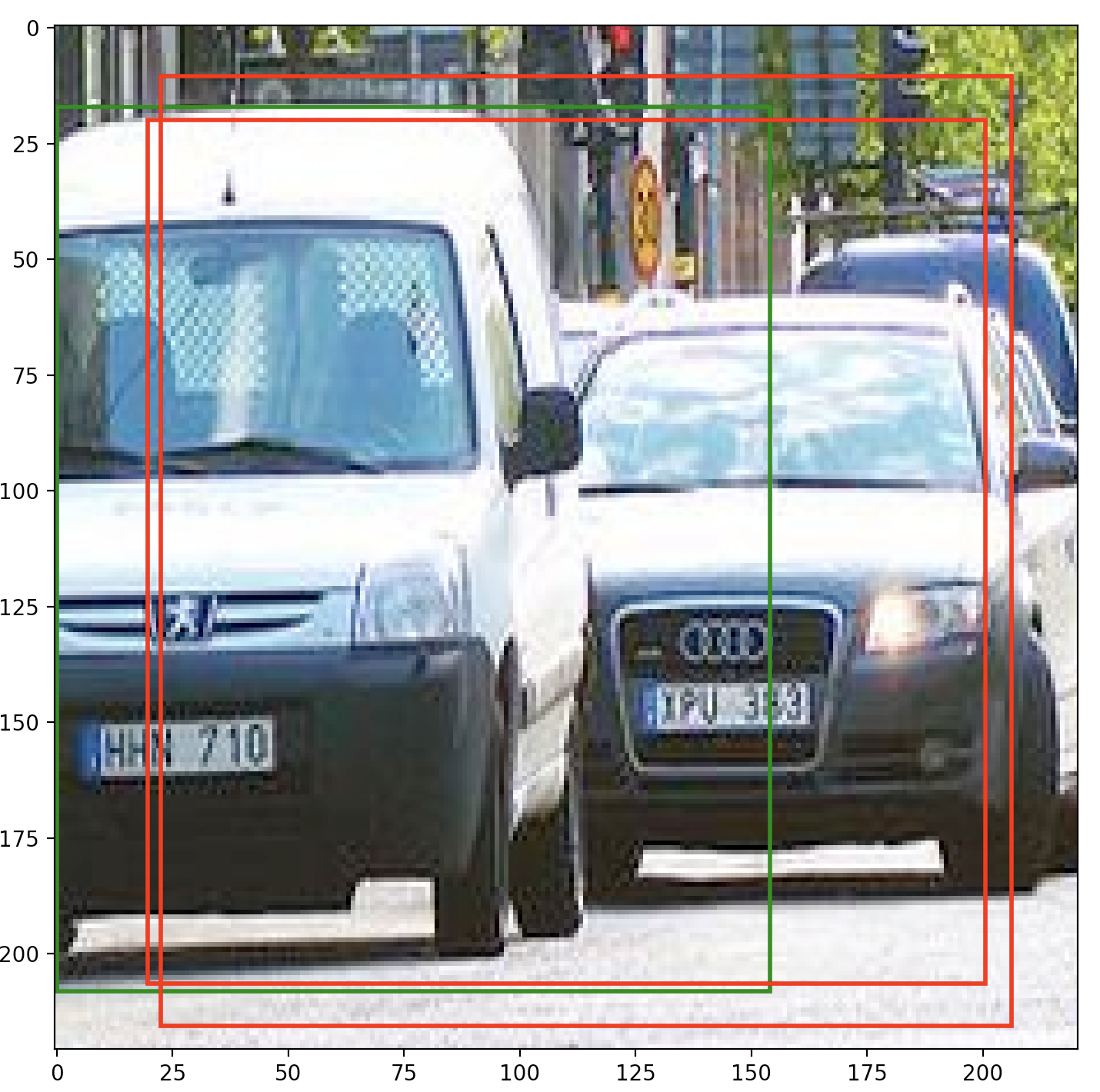

We see additionally the visualizations of the localization of these classification of two cars. We see that:

Regression:

Figure 4. Model training metrics for regression for the last 5 epochs

| Epoch | Training Loss |

|---|---|

| 36 | 367.07110595703125 |

| 37 | 364.2298278808594 |

| 38 | 362.7608642578125 |

| 39 | 361.27398681640625 |

| 40 | 353.4579772949219 |

Figure 5. (red) Predicted Bounding Box. (green) Ground Truth Bounding Box

Figure 6. The Predicted Boxes against the Ground Truth Boxes

| Predicted Box | Ground Truth Box |

|---|---|

| [22.466618, 10.45407, 183.74428, 205.123332] | [0.0, 0.0, 221.0, 221.0] |

| [19.590916, 19.863789, 180.85982, 186.44931] | [0.0, 0.0, 221.0, 221.0] |

5. Reflection and Discussion

The model performed extremely well in general classification reaching thresholds of above 93% in label prediction for testing. The regression component remained difficult in aptly scaling these bounding boxes to capture the information for multi-classification. While our model performed the best for single class regression such as car per class regression where regressions of bounding boxes ranged for car traffic light and stop signs were more problematic to manage. In future work we would hope to focus on creating many scales for the image as noted in the paper which would exponentially increase the amount of bounding boxes to work with and enhance our prediction for multi-classification. We would also look to deploy a custom detection training component where false positives would be rejected thus furthering our predictive powers. Additionally, the authors of the paper recommend expanding back-propagation for localization throughout the entire network (we currently freeze the Overfeat training weights).

Object detection remains a fundamental use-case for computer vision and carries a diverse range of applications in various fields: the Overfeat model proposes an exciting architecture for this detection and look forward to future iterations on the design.

We are decently happy with the result of the project though we are disappointed that the regression did not perform as well as we would have hoped. During the project, we had to make a couple of pivots as the algorithm failed to learn the “background” class. For localization our algorithm has performed reasonably well and has mostly attained the target goal in terms of classification and localization. If we had more time, we would have attempted the work on other datasets, perhaps ones with less noise. We would also attempt to train the model to recognize the “background” class for the purpose of object recognition.

The project exposed us to the challenges faced in real-world deep learning work where the data is not neatly presented and models are not guaranteed to work. The process of working with preprocessing of data and tuning the model and reducing the model has shown us how delicate the art of training a machine learning algorithm can be.

6. Code Repository

Our codebase is accessible on GitHub at: https://github.com/dwei7/DL-Final-Project/tree/oli

7. References

- Sermanet Pierre & Eigen David & Zhang Xiang & Mathieu Michael & Fergus Rob & Lecun Yann. (2013). OverFeat: Integrated Recognition Localization and Detection using Convolutional Networks. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (Banff). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1312.6229

- P. F. Felzenszwalb R. B. Girshick D. McAllester and D. Ramanan "Object Detection with Discriminatively Trained Part-Based Models" in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence vol. 32 no. 9 pp. 1627-1645 Sept. 2010. DOI: 10.1109/TPAMI.2009.167

- Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks by Shaoqing Ren Kaiming He Ross Girshick and Jian Sun. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.01497

- Single-Shot Detection for Real-Time Object Detection by Wei Liu Dragomir Anguelov Dumitru Erhan Christian Szegedy and Scott Reed. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1512.02325